hfjgfhjfj

PRESS RELEASE: Somewhere in the Middle: Donald Martiny sets the stage for a new dance by Amy Hall Garner and the Paul Taylor Dance Company

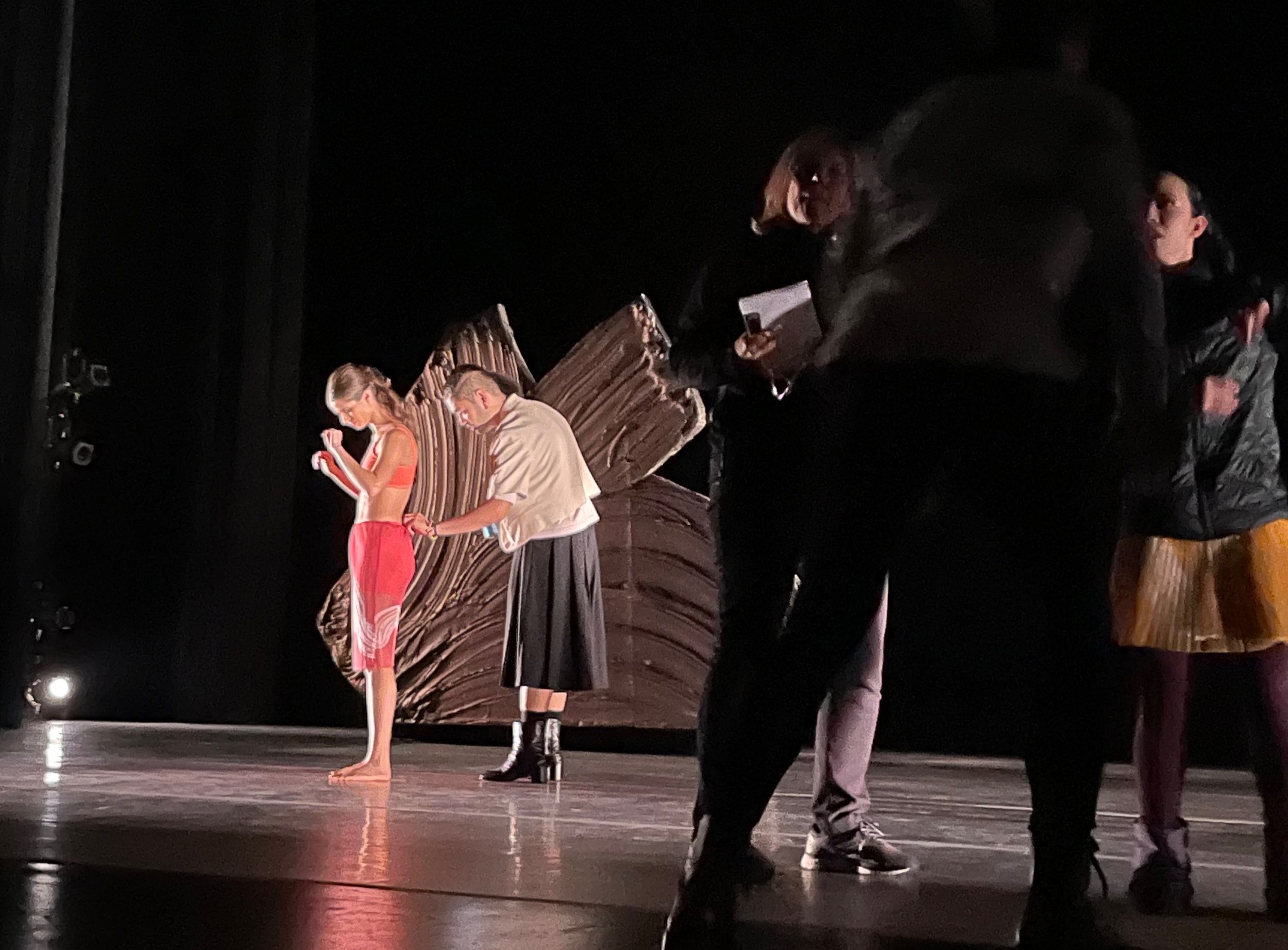

The Paul Taylor Dance Company’s new commissioned dance, Amy Hall Garner’s Somewhere in the Middle, with set design by Donald Martiny, will have its World Premiere at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center on November 3, 2022 at 7pm. A second performance will take place November 11 at 8pm. Book tickets by clicking here and using promo code MARTINY10.

"Jazz and Modern Dance are considered American art forms,” noted Ms. Garner. “When people think of classical western music and dance, most associate these art forms with nationalist European cultural traditions. By contrast, the United States – a nation made up largely of immigrants from throughout the world – has evolved these two forms through its inherent multiculturalism. With my new dance I wanted to marry the Taylor movement DNA to the inherent qualities of the jazz idiom, resulting in an organic, authentic partnership between music and movement."

Martiny’s work aligns with Garner’s ambition. He’s been called “a gestural abstractionist,’ which suggests comfort in the arena where dance and jazz collide. His ambitious set design for Somewhere in the Middle takes the form of his signature ‘frozen brushstrokes,’ three-dimensional explorations of paint’s ability to convey both movement and stillness. His bold, colorful set elements combine magically with costumes by Mark Eric, and are stunningly illuminated by lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton.

PTDC Artistic Director Michael Novak said, “Garner's dances thrill audiences through their architecture, athleticism, musicality, and visual momentum, and her new dance demonstrates our ongoing commitment to facilitating work that enables the performing and visual arts to shine together. An alchemist, Amy has assembled an extraordinary team. Don is a remarkable collaborator, and we’re delighted he’s joined the Taylor Family.”

Martiny joins a rich tradition of artists designing for the Paul Taylor Dance Company, extending the legacy forged by Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, and Alex Katz.

PRESS RELEASE: Time Space Existence (A Retrospective) at Madison Gallery

In honor of Donald Martiny’s inclusion in the PERSONAL STRUCTURES Exhibition at the 59th Venice Biennale, Madison Gallery announces TIME SPACE EXISTENCE a retrospective of the artist’s important works dating from 2013 to the present. Many of these works were included in Donald Martiny’s first major solo exhibition, Freeing the Gesture at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, and are available for private acquisition for the first time.

“In the 1950s, artists like Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline elevated the gesture to the position of the protagonist in abstract expressionism. In the 21st century, Donald Martiny advances that idea considerably further by freeing the gesture of gestural abstraction from the substrate which, heretofore, provided the context that brought gesture to life. Working with polymers and dispersed pigments, Mr. Martiny has developed a methodology that enables him to isolate his sumptuous, almost sculptural, brushstrokes and lift them off the page, so to speak. The nature of his material is such that Mr. Martiny can work on a much larger scale than if he were dependent on a canvas surface; indeed, each singular brushstroke might range from two- to as much as six feet in length. Installed, these compelling monochromatic gestures immediately breathe a new kind of life into the gallery space.

Historically, Mr. Martiny’s work to date fits right into the continuum of monochromatic painting, a contemporary reductive movement that has advanced the concerns and broadened the interests of the classic Minimalists of the 1960s and of the much earlier Suprematists, who openly sought the ‘death of painting” with their monochromatic efforts. Mr. Martiny belongs to a family of painters, including such luminaries as Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko, Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman, Frank Stella, and Olivier Mossett. Amazingly, these distinguished artists brought something noticeably different to this admittedly singular and restrictive approach to painting. Before Mr. Martiny, though, each of these other great painters relied on manipulating the relationship between canvas and pigment to achieve subtle, nuanced differences in each painting. Mr. Martiny has greatly expanded the painterly agenda by taking the brushstroke completely off the canvas entirely. I applaud his commitment to furthering the monochromatic agenda and his ability to make fresh, new work that acknowledges, rather than negates, decades of previous good work. Rather than hastening the death of painting as Rodchenko forecast, monochromatic painting has already enjoyed a long lifeline and, in the hands of Donald Martiny, is alive and well.”

Charles Shepard III, Director, Ft Wayne Museum of Art.

For more information visit www.madisongalleries.com.

PRESS RELEASE: Donald Martiny's "Moment" to be exhibited in Venice during the 59th Venice Biennale

Madison Gallery will be exhibiting Donald Martiny’s seminal work, Moment as part of the Personal Structures Exhibition at Palazzo Bembo, April 23 through November 27, 2022, in conjunction with the 59th Venice Biennale.

Art and spirituality have always been intimately connected, not only in the way they address the nature of our existence, but also because of their ability to register deep within us. Together they viscerally connect us to an inner feeling, spirit, or vital essence. This work by Donald Martiny strives for what Kandinsky described as the “vibration of the human soul.”

The painting titled Moment is by far the most ambitious work Martiny has made to date. The painting is made of multiple elements, its creation demanding over one hundred liters of paint to produce. Working on the floor, the artist moves physically inside, around, and through the varied components of his compositions within the paint, pushing the viscus color across surfaces with his hands, arms, and body.

The work is figurative in the sense that dynamic gestures relate to the human form in landscape. Shaped paintings have typically been made through an additive process, by applying paint to predetermined shapes. Martiny’s work challenges that notion. His gestures and completed compositions gain their power through a hybrid subtractive process that determines the final profile of the work.

From a formal perspective, his process forces us to question established definitions which define our fundamental understanding of painting. The art of Donald Martiny exists somewhere between painting and sculpture. We are confronted with a singular brushstroke, huge, a seemingly spontaneous, lavish eruption of color and texture on the wall.

This exhibition was made possible by curator Lorna York and Madison Gallery.

A spellbinding conversation with Donald Martiny

Donald Martiny is an American Contemporary painter and fine artist, who is known for his use of color in his abstract paintings. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in art galleries and art spaces such as the Conny Dietzschold Gallery, the Cameron Art Museum, the Diehl Gallery, Market Art + Design Hamptons, and many more. His work is held in collections such as the Grahm Gund Family Foundation, One World Trade Center, the Newcomb Art Museum, and elsewhere. Martiny has lectured at Cornell University and at the Ackland Art Museum. His artwork has received press and been in publications internationally, most recently he has been featured in Architectural Digest. I had the pleasure and honor to ask Donald what has been his most challenging project as of yet, what drew him to making abstract art, and how he hopes people feel when they see his art.

UZOMAH: How do you approach the process of designing and creating artwork that you are asked to create?

DONALD: I keep a regular schedule in the studio working every day, seven days a week, from around 9:00 AM until 7:30 PM. I believe the best ideas and inspiration come from the work, the doing.

As I work I am in constant dialogue with the paintings and they tell me what to do. They ask questions, or present new opportunities and challenges. I am constantly pushing myself, my processes, my materials, and my abilities as an artist.

U: What has been the most challenging project you have worked on?

D: There have been many. One that is easy to talk about was when I was commissioned to make two monumental paintings to be permanently installed in the lobby of One World Trade Center in New York City. The two paintings were to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the opening of the building. Because the paintings were too large to pass through any of the doors in the building, we decided to convert the lobby into a studio space where I would make the paintings on site.

Prior to that, no one had ever watched me paint. Painting requires a lot of focus and concentration. The lobby of One World Trade Center receives nearly twenty-five thousand visitors each day. That was a big challenge for me. Additionally, I only had a limited amount of time to create the paintings and allow them to dry enough to install… and nowhere to hide if anything went wrong. Thankfully, everything went beautifully, and I am very proud of the works.

U: How do you use abstract to display basic action and movement?

D: The gestures or brushstrokes in my works are made from my body moving through the paint.

I am not depicting images of movement, I am creating tracks or evidence of movement that actually happened. The marks are defined by the physicality of my body at the time. I think of the paint or color as pure sensation or feeling. I am pushing around feeling with my hands.

Moving is an expression just as the color is. It all comes together, drama, movement, light, color, time, dance, much like a film or an opera.

U: What are some things that made you want to be an artist that keep you going when days might provide you with reasons not to create?

D: I responded powerfully and viscerally to color at a very early age. Even though there was no art to speak of in our family home when I was growing up, and I didn’t have any concept of what an artist was, I knew I was interested in making things with color and form. I have always loved to draw. I first had my work exhibited in a professional art gallery when I was twelve years old.

U: What type of objects do you feel when creating and hope others might also see within your art?

D: I paint from the heart. That said, I try to make sure my work has a dialogue with the history of paintings. I look, read, study the history of painting religiously. Lately, I have been particularly interested in the Venetian school of painting: Titian, Giorgione, Tintoretto, and Veronese. They brought painting to life with their evident brushwork, their “colorito.”

U: What about art drew you to abstract?

D: I enjoy all kinds of art, both abstract, image-based art, objects, etc.

I make abstract art because I want to create experiences rather than illustrate narrative stories or present symbols to represent something other than what they are.

U: How do you hope other people will feel when they look at your art?

D: It is a joy when people respond to my work. A work is successful when I respond to it myself. I make works I would like to live with myself. When others respond to my work I feel we are sharing something. I think it is remarkable when someone from a faraway place, who comes from a very different culture, speaks a different language, shares an experience with me.

That is something very special and touching.

U: How do you keep the motion and action found in life in your art?

D: Movement is life, stillness is the opposite. My work celebrates life. I have no straight lines in my art. Everything is moving.

U: Can you describe your most acknowledged stroke seen throughout your most prolific pieces?

D: I imagine my most known and seen works are the two paintings permanently displayed in the lobby of One World Trade Center in New York City. They were installed to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the opening of the new building. It is truly an honor to have my work displayed in the lobby of one of the most iconic buildings in the world.

Thank you very much for the opportunity to talk about my art practice with you. It was a pleasure.

The brushstroke that makes eternal your art experience

“I prefer to create visceral experiences rather than intellectual explanations or narratives” D. Martiny

How many art exhibitions have you visited? I guess you have seen so many that you have lost count. However this time it’s different. Donald Martiny’s artworks have a kind of magical power: in each of them you can recognize a specific point in the author life. His paintings make eternal even the easiest life moments in an effort to celebrate every frame of the human existance. From the biggest events to the smallest ones. His creations are two-dimensional and three-dimensional: they are paintings and sculptures at the same time. In fact they emerge from the wall in which they are displayed. The artist was born in Schenectady (NY) in 1953 and currently works in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. His artworks are collected internationally and are shown widely. I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing him just some weeks before the opening of his last art exhibition in Venice (“PATHWAYS” – 10/09-10/10/2021 Scala Contarini del Bovolo San Marco). He has told us about his poetic and inspiration, his particular creative technique and last but not the least his relationship with some great art history masters.

Have a nice reading.

E.R. We can place your artworks between painting and sculpture. Your brushstrokes "frozen" your gestures in a particular moment of your life. Which intimate creative poetics underlies in your creations?

D.M. For me, movement is life; stillness indicates the absence of life. I want to celebrate life. My paintings are living events, movement, time, and my own physicality, captured in paint.

E.R. Your brushstrokes are self-supporting, without the need for a canvas. Why did you choose this particular effect?

D.M. I create objects from gestures. My works are a dialectical challenge; an inquiry into metaphysical contradictions. Throughout art history, the traditional rectangular shaped canvas has been seen as a portal, a frame to a door or window that the viewer looks through to experience the art. I intend to move the experience in front of the window rather than behind the window. I want to involve the viewer as well as the space surrounding the work. That is why scale is very important to me. Large paintings invite the viewer inside, while the experience with small artworks the viewer is outside looking in. I have noticed that when people respond to artworks, they tend to approach and inspect them closely. I believe we do this because we want to participate in the work. We want to see the brushwork and see how the painting was made. During a recent exhibition of my work in Padua, Alessandro Deponti (my art dealer in Milan) and I visited the Scrovegni Chapel, a masterwork beautifully painted by Giotto in 1305. I was particularly struck by his Lamentation of Christ. In that panel Giotto invented a remarkable device to invite the viewer into the painting. The central foreground crouching figure is the first use of the rückenfigur or staffage. Much later, in 1808, Caspar David Friedrich revisited the idea in his famous painting, Der Mönch am Meer. With their back facing the viewer of the painting, the rückenfigur device looks into the work and invites the viewer to place themselves in the exact spot (substituting the rückenfigur with themselves) in the painting. This is a long explanation but it gets to the idea that I am trying to invite the viewer into the painting and also that I look to art history to find inspiration and ideas for my work. My art attempts to create powerful and moving experiences for the viewer. I prefer to create visceral experiences rather than intellectual explanations or narratives.

E.R. This decision has led you to a long research for finding the right pictorial material which can reproduce the fluidity of the brush and, at the same time, being hard to the right point to avoid breaks. Which kind of impasto do you use?

D.M. I work with a specially made long-chain polymer. It makes an exceptionally viscus paint. Sometimes I grind my pigments using a sophisticated ultrasound machine that can create a very fine grain, enabeling me to pack the paint with the maximum amount of color. I paint on aluminum because aluminum doesn't expand or contract with changes in temperature or humidity. My paintings can be installed outdoors without any problems.

E.R. Have some great masters of the art history influenced your path? If so, which ones?

D.M. Absolutely! I would say the painters of the Venetian School, Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Bellini, with a particular emphasis on Tintoretto. I love the fact that according to Carlo Ridolfi his biographer, Tintoretto had a sign in his studio that read,"Colorito di Tiziano, disegno di Michelangelo.” (Ridolfi, Carol, Vita del Tintoretto, 1642, publication). I couldn't agree more. I often refer to Titian or Michelangelo, among many others, for ideas or inspiration. I have always found the innovators in art to be the most interesting. I look at the history of art in a very atemporal way and find ideas and inspiration from all of it. A few artists I particularly focus on are Greek artists like Apelles of Kos, Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus, to Ellsworth Kelly, Judy Pfaff, Frank Stella, Anselm Kiefer, and Bill Viola. I also often look to Caspar David Friedrich, Kazimir Malevich, Barnett Newman, and Willem de Kooning.

E.R. Can you describe us an artwork currently shown on the Artsail platform, where you are represented by ARTEA Gallery, which best reproduces your creative philosophy?

D.M. Artsail is a wonderful platform that is so rewarding and interesting to explore. ArteA Gallery features a work of mine titled, Nushu, 2019 that is 91 x 112 cm. This painting made with seven red hues is an excellent example of how my work differs from most shaped paintings. Artists like Frank Stella, Elizabeth Murray, Ellsworth Kelly, George Sugarman, Mary Heilmann make their shaped paintings by building a form before painting it. My process is the opposite. I work on a large sheet of aluminum where I paint very freely, spontainiously, and gesturally, allowing for drips and pentimenti. Once the paint is dry enough, I cut away the negative spaces. The resulting freely painted gesture determines the form of the painting. I come from a serious study of the gestural abstract work of the modernists but lived through the ironic and somewhat cynical post-moderns. My work is not negative, ironic, or cynical at all. I am striving for authenticity and a poetry of deeply felt passion.

E.R. On the 10th of September your solo show will open in Venice. Its title is "PATHWAYS". Can you tell us something more about it?

D.M. I believe the exhibition's title was conceived by Gianluca Ranzi, who generously and brilliantly curated the exhibition. He is a wonderful curator and writer who I had the great pleasure to meet at my first solo exhibition at ArteA Gallery in Milan. For me, "PATHWAYS" is a marvelous title as it touches on many different interpretations. Pathways are connectors; they take you from one place to another. They imply exploration and connections. Some are clear and well established, sometimes we make our own new pathway. The path could be the path of the brush and paint, the path of art history, the path of the artist, or the path of the viewer. I like to think of PATHWAYS as connection between the artwork, the viewer, and the artist. I was very excited to learn that my work will be shown in dialogue with the work of Tintoretto. How timely as he was working at a time the world was challenged by a plague just as we are now. I personally feel very connected to Tintoretto as he, perhaps more than any other artist of his time, worked in a very painterly, gestural, and immediate way. His pivotal painting, The miracle of the Slave or Miracle of St. Mark painted in 1548 (commissioned for the Scuola Grande di San Marco, now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice), is for me among the greatest works in the history of art. The remarkable invention of Saint Mark flying over the viewers into the painting is nothing short of miraculous. This invention forces the viewers to participate in the work rather than be casual observers of the work. Perhaps the exhibition's title, "PATHWAYS," is about forging a connection between Jacopo Robusti (called Tintoretto) and Donald Martiny.

Donald Martiny and Tintoretto: Baroque Abstraction

As Donald Martiny tells us, his new abstraction, an ingenious fusion of painting and sculpture, was inspired by Tintoretto’s The Miracle of the Slave, 1548, a painting depicting the miraculous moment when St. Mark descended from the sky—heaven—to rescue a slave—by making him invulnerable—about to be martyred. The Venetian Tintoretto was called Il Furioso—he painted with furious energy and decisive swiftness. His brushwork, forceful and conspicuous—painterly and expressionistic, we would say—seemed to exist for its own pure sake. It was unprecedented, art historians tell us, for his gestures, dramatic and conspicuous, had a life of their own, independently of the life they gave to the figures, an emotional intensity independent of the emotions of the figures. Tintoretto’s paintings have been called proto-mannerist, but they are peculiarly baroque—far ahead of their times, for as the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin wrote, “baroque is movement imported into mass” (embodied movement, one might say)—which is also what the modernist critic Clement Greenberg called “painterly abstraction,” in a sense baroque painting stripped of representational purpose. Certainly the twisting figures of Baroque sculpture have something in common with the twisting, not to say convoluted, “figures” Martiny’s works cut. Painted sculptures?, sculpted paintings?—they are autonomous gestures, all the more grand because they are simultaneously three- and two-dimensional, giving them what the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead calls unusual “presentational immediacy.” There is certainly something “furious”—hyper-energetic, manic (no doubt under aesthetic control, aesthetically domesticated yet wildly driven)--about Martiny’s work, miraculously holding its own against—vigorously defying—the luminous white wall on which it miraculously holds its heavenly own, the way Tiepolo’s St. Mark does, a massive grand gesture disguised as a human figure, compressed into an oddly fluid, even amorphous shape.

To read Martiny’s work as an abstract distillation or secular translation of Tintoretto’s representational and religious painting—the shadowy red robe of the saint reductively transformed into a powerful grand gesture, the blue sky and luminous horizon seamlessly fused in less dramatic, less poignant gestures, resulting in a work more physically in-your-face than Tintoretto’s spiritual painting, comparatively static and self-contained compared to Martiny’s abstract work, with its animated, seemingly random gestures (it certainly more emotionally engaging and takes more creative risks)--is to sell its significance short. It argues for the continuity between representational and abstract art, more broadly, the inseparability of traditional and modernist art. Martiny’s gestures are simultaneously epic and lyrical, bridging the gap between—reconciling--American abstract expressionism and European abstraction lyrique, more particularly the aggressiveness of the New York School and the libidinousness of the School of Paris. It quintessentializes gesturalism. It is at once centrifugal and centripetal—a sum of dervishing gestures that hold together, attached to each other even as they seem to move apart—a balance of forceful forms ingeniously coordinated—“classically” harmonized, one might say, even as they are “romantically” at odds. The work is subjective signature painting objectified as sculpture—or is it object-like sculpture subjectified as expressionistic painting? Martiny’s painting/sculpture—sculptured painting, painterly sculpture, inviting us to re-imagine both—is a masterpiece of dialectical thinking.

Donald Kuspit

Time Space Existence at the 59th Edition of the Venice Biennale, 2022

Madison Gallery will be exhibiting Donald Martiny at the 59th Venice Biennale, April 23 through November 2022 in partnership with the ECC European Cultural Centre at the Palazzo Bembo.

The art of Donald Martiny exists somewhere between painting and sculpture. We are confronted with a singular brushstroke, huge, a seemingly spontaneous, lavish eruption of color and texture on the wall.

Space: Traditional Western painting from the time of Giotto until Courbet created the illusion of space using Filippo Brunelleschi’s ideas of perspective. This type of space offered the viewer the opportunity to enter the illusory, albeit fictional picture space to experience the art. I intend for my works to exist in the same space as the viewer; to interact directly as an object with the environment and the viewer.. The forms of the work are in dialogue with the wall, the room, and the viewer. In Germany in 1808 Caspar David Friedrich brilliantly synthesized and amalgamated space in his painting Der Mönch am Meer and later with Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer by inviting the viewer to place themselves into the painting through the use of a Rückenfigur. Barnett Newman understood this very well when he painted his masterwork Vir Heroicus Sublimis in 1951. Through the use of free-standing paint-sculptures my work is in dialogue with the history of the use of space, the history of painting, and with these paintings in particular.

Time: In photography the shutter speed of 1/1600th second is typical to freeze action and capture an instant in time. While photography captures the image of an instant in time, a painting captures an event in time. Rather than producing an image of a gesture or mark, my paintings are the result of an event. The event happens over an extended period of time. By inviting the viewer into the painting, to become a collaborator or participant rather than a casual viewer the works offer a multifaceted and complex experience similar to the experience one might have wandering through a cathedral rather than the usual glance, glimpse, or cursory look. What I have in mind is a different kind of experience: not just glancing, but looking, staring, gazing, sitting or standing transfixed: forgetting, temporarily, the errands you have to run, or the meeting you’re late for, and thinking, living, only inside the work. Forgetting time, the past, the future, only existing in the present.

Falling in love with an artwork, finding that you somehow need it, wanting to return to it, wanting to keep it in your life. This kind of experience requires time and a willingness to be in dialogue with the work; to have an ongoing relationship with it. While the painting itself may be unchanging, the viewer may find they change quite a bit over time.

Solo Exhibition: Tristan's Chord at Madison Gallery

Madison Gallery presents TRISTAN’S CHORD, Donald Martiny’s 4th solo exhibition with Madison Gallery, so titled for the opening phrase of Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde. This collection consists of multi-components, harmonizing in minimal, tonal work and made of polymer and pigments. The disposition of the material and the demonstration of the drawing of the line are like muscular acts that present themselves. Roland Barthes referred to this type of self-presentation of the material process-based nature of artistic gestures as ‘scription’. The materiality of the gesture—from density to color scheme—is not there to be overcome reflexively: it is the inextricable means of artistic debate. In other words, ‘matter’ (material) that matters (theme).

“The art of Donald Martiny exists somewhere between painting and sculpture. We are confronted with a singular brushstroke, huge, a seemingly spontaneous, lavish eruption of color and texture on the wall. It is the mark distilled from painting, the formerly minute detail writ large, what we usually discover as a hidden and obscured part of the whole is made to be the whole itself, the entire work a gesture on the wall.

Such dramatic works are fit for public art – Martiny is currently preparing to install a large work on the exterior of a building in Raleigh, North Carolina and is well known for his permanent displays in the lobby of One World Trade Center in New York City. But they also lend themselves to powerful aesthetic experiences in more intimate galleries, as will be evident in upcoming solo shows in February 2021 at Madison Gallery in Solana Beach, California and in March 2021 at the Scala del Bovoli in Venice, Italy.

How did Martiny come to these oversized gestural works? Normally, the canvas frames the work, or else is itself framed, and the plane delineated by the canvas’ edge creates the ground from which a figure will arise. Sometimes the figures are strictly representational of human forms, of flora and fauna, and other times we are treated to compositions suggestive of moods, abstract expressions of a concept or emotion and so on. Whatever the content, whatever level of literalness present within the edges of the canvas, there is something that stands out from the ground of the canvas. The canvas itself sinks into the background and by becoming this background makes it possible for whatever appears to the viewer to appear. But there is no canvas to form the ground of Martiny’s work. The wall on which the work is mounted becomes the ground, the room itself, the gallery or museum is the ground.” - Donovan Irven of White Hot Magazine

Donald Martiny, TRISTAN’S CHORD

Solo Exhibition at Madison Gallery, Solana Beach, CA

Feb 27, 2021 - Apr 30, 2021

Interview with Donovan Irven for Whitehot Magazine: Donald Martiny, or Figures Without Ground

The art of Donald Martiny exists somewhere between painting and sculpture. We are confronted with a singular brushstroke, huge, a seemingly spontaneous, lavish eruption of color and texture on the wall. It is the mark distilled from painting, the formerly minute detail writ large, what we usually discover as a hidden and obscured part of the whole is made to be the whole itself, the entire work a gesture on the wall.

Such dramatic works are fit for public art – Martiny is currently preparing to install a large work on the exterior of a building in Raleigh, North Carolina and is well known for his permanent displays in the lobby of One World Trade Center in New York City. But they also lend themselves to powerful aesthetic experiences in more intimate galleries, as will be evident in upcoming solo shows in February 2021 at Madison Gallery in Solana Beach, California and in March 2021 at the Scala del Bovoli in Venice, Italy.

How did Martiny come to these oversized gestural works? Normally, the canvas frames the work, or else is itself framed, and the plane delineated by the canvas’ edge creates the ground from which a figure will arise. Sometimes the figures are strictly representational of human forms, of flora and fauna, and other times we are treated to compositions suggestive of moods, abstract expressions of a concept or emotion and so on. Whatever the content, whatever level of literalness present within the edges of the canvas, there is something that stands out from the ground of the canvas. The canvas itself sinks into the background and by becoming this background makes it possible for whatever appears to the viewer to appear.

But there is no canvas to form the ground of Martiny’s work. The wall on which the work is mounted becomes the ground, the room itself, the gallery or museum is the ground.

Read the rest of the interview by clicking here.